Museum

Visiting the Museum

The Manzoni Museum has recently been redesigned using a more scientific approach, according to the latest guidelines in museology and museography, with the help of the Board and Advisory Committee of Casa Manzoni, under the supervision of Professor Fernando Mazzocca.

The Museum, curated by Michele de Lucchi, offers a tour round Casa Manzoni in ten sections offering several different itineraries through the life and works of the writer, through the furnishings and works of art on display in the rooms: from the family to portraits, from the landscapes found in The Betrothed to his passion for botany, from his friends to the writers he in turn inspired, from the bedroom - which is as he left it - to the study which witnessed the birth of his novel.

Room 1

The family

Alessandro Manzoni, officially the son of Pietro Manzoni and Giulia Beccaria, grew up ‘with no family’: but as fate would have it (which he himself would have called 'Providence', which can bring good out of the mess that is sometimes human affairs), he was in fact the descendant of the two most famous Milanese families, the Beccarias and the Verris, who between them made a huge contribution to the new legal and cultural civilization of Europe.

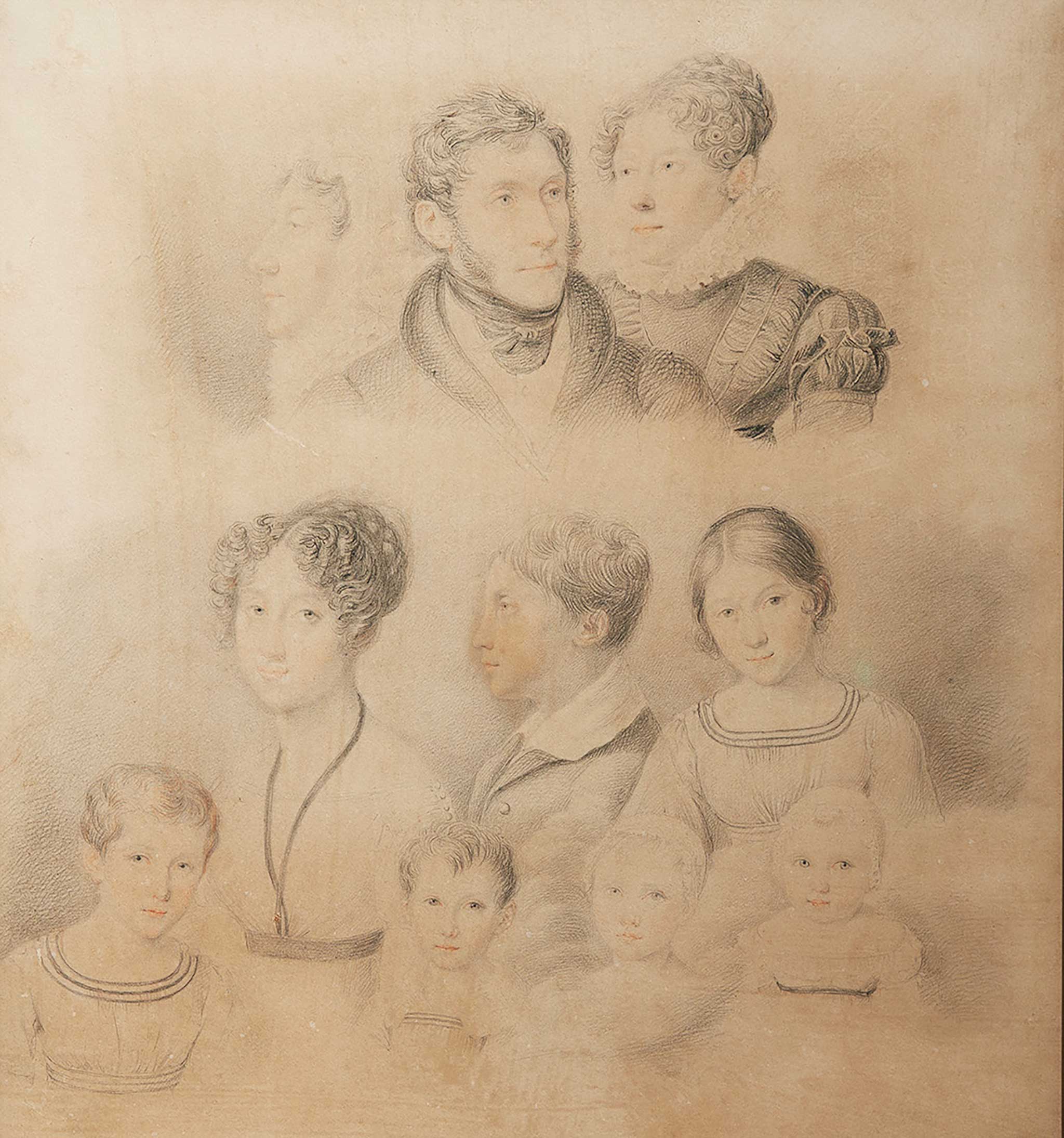

Gulia finally atoned for her lengthy neglect of her exceptional son after putting him into boarding school in 1791, when she summoned him to Paris in 1805 and started to develop a proper relationship with him. Doubtless she would have told him, according to Carlo Imbonati’s ‘virtuous’ account at any rate, that his biological father was Giovanni Verri, the worldly brother of Pietro and Alssandro. Manzoni’s dream of seeing children of his own enjoy the childood he himself had never had (the memory of a brief meeting with his famous grandfather Cesare Beccaria aged six was to remain with him), began to be realized when, on 8 February 1808, aged twenty-three, he married Enrichetta Blondel, the daughter – not yet seventeen – of an industrialist from Geneva and owner of a silk mill in Casirate d'Adda.

His firstborn, too, was named Giulia, after her grandmother, who came to live with Alessandro and Enrichetta and finally establish a stable family unit. Giulia was born in Paris on 23 December 1808, and was soon followed by Pietro, Cristina (the first birth to be born in Via Morone), Sofia, Enrico, Clara and Vittoria. The pencil and crayon drawing by Ernesta Bisi depicts a picture of a happy family - Clara, who died aged just two, is depicted with a halo – in the years when Manzoni was working on the first version of The Betrothed. Later on another son Filippo was born, and finally, on 13 July 1830, Matilde. The death of Enrichetta, Manzoni’s ‘only beloved' (the epithet chosen by Manzoni to evoke the inimitable love of Christ for the Virgin Mary in his unfinished Il Natale del 1833 is used advisedly here) on 25 December 1833, was the first in a series of family bereavements, soon to be followed by three of their daughters: Giulia (the mother of Alessandrina) aged just 26, Cristina (the mother of Enrichetta) and Matilde; and then, aged twenty-eight, Sofia (the mother of Antonio, Alessandro, Giulio and Margherita).

Only Vittoria, who married Giovan Battista Giorgini, and Enrico were to outlive their father. Enrico, an impulsive investor with interests in the silk industry, was, along with the dissolute Filippo, the source of much sadness for Manzoni, and it was he who in 1874 decided to put Casa Manzoni up for sale, to safeguard the future of his own children who had not yet come of age.

Room 2

The portraits

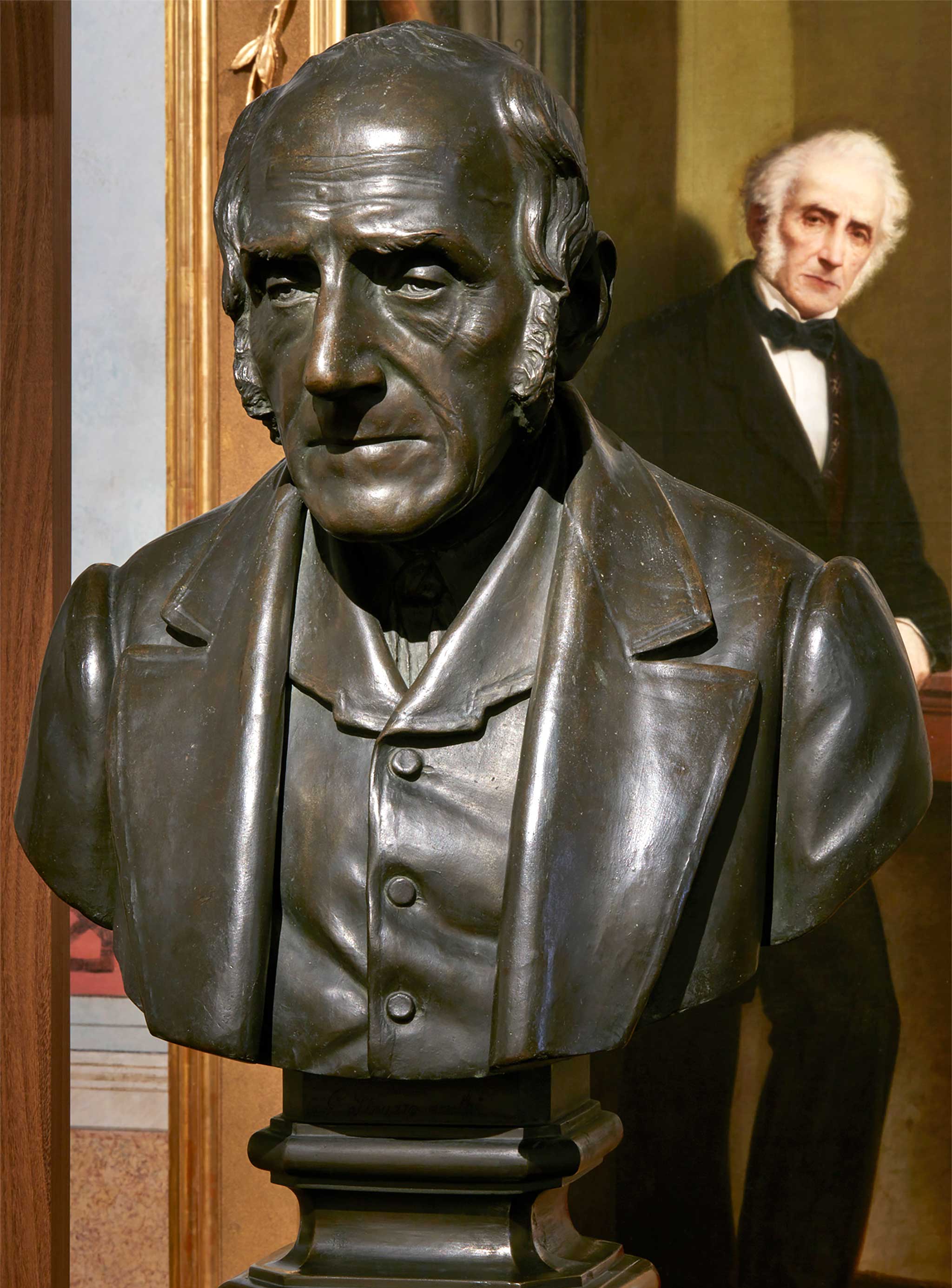

Although Alessandro Manzoni was by nature disinclined to sit for portraits, his fame from an early age meant that a considerable number of portraits survive, in various forms and media, ranging from painting to sculpture, from drawings to etchings, from lithographs to photos, as the works from different dates collected in this room show. For the most part the portraits were made without Manzoni’s consent, the author playing no active role in what would now be referred to as the management of his image rights.

The only exceptions are the two finest and justly most famous portraits, for which he did agree to sit. The first, painted in 1835 by Giuseppe Molteni, together with Massimo d'Azeglio (who was responsible for the backdrop depicting Lake Como), is kept at the Biblioteca Braidense Nazionale; while the second, the popular portrait commissioned by Manzoni’s stepson Stefano Stampa and painted by Francesco Hayez in 1841, is on show at the Pinacoteca di Brera, and represented here in a period photograph reproduction.

In this room we find a series of portraits showing Manzoni at all stages of his life. The earliest were largely private exercises, while those from his later years and after his death, by which time he was already recognized as one of the fathers of the nation, have a more celebratory dimension.

The monumental portrait painted by Carlo De Notaris in 1874, the year after Manzoni’s death, is notable for its ceremonial qualities, while the drawing by Stefano Stampa records his stepfather in a private moment, and is more touching.

The sculptures, meanwhile, show us the public Manzoni, like in the small bronze group of which other versions exist, depicting the historic meeting, 25 March 1862 in this very house, between Garibaldi and the man who, as the general put it, ‘so honours Italy’; or the copy of the bronze monument by Francesco Barzaghi made in 1833, and situated in Piazza San Fedele before the church at which Manzoni worshipped.

Room 3

The reception of The Betrothed in the visual arts: painting, sculpture and illustration

The extraordinary popularity enjoyed by The Betrothed from as early as the first edition published in 1827, soon resulted in equally extraordinary success in terms of visual representations. The places, characters and principal episodes were all depicted in paintings, sculptures, and even the cycle of frescoes made by the painter Nicola Cianfanelli between 1834 and 1837, that decorate the Meridiana royal apartments of Palazzo Pitti in Florence, having been commissioned by the Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany who was a great admirer of Manzoni. But above all it was the illustrations that accompanied the book editions, and in particular the unbound series of etchings or lithographs which were often framed and came to adorn houses from the Alps down to Sicily, that were responsible for spreading images of a world which had soon become part of the Italian national conscience.

The paintings shown here are exemplary in the sense that they represent two of the best-loved episodes in the novel. ‘L’addio a Cecilia’ (‘Farewell to Cecilia’), shown at the Brera Exhibition in 1857 by nobleman and amateur Carlo Belgiojoso; and another heart-rending farewell, that of Lucia to her home mountains, which Luigi Bianchi depicted in appropriately sentimental fashion. This and the other important moments in the novel’s great historical design are found in the more popular illustrated series, such as the lithographs made by Gallo Gallina from Cremona and published by Ricordi between 1827 and 1828, featured here in the rare hand-coloured versions.

The series by Gallina, which was one of the most popular, is notable for the accuracy with which this artist, who was expert in the genre of historical paintings, was able to faithfully and accurately depict the places - landscapes as well as interiors - and customs of the seventeenth century, in which the novel was set. His rendering of the epic dimension in the broader scenes in which Renzo appears as the protagonist and in his own way the hero are particularly impressive.

Room 4

Teresa and Stefano Stampa’s illustrated books and the 1840 illustrated edition of The Betrothed

Manzoni's second marriage – in 1837 – to Teresa Borri, the widow of Count Stefano Decio Stampa, saw a wind of change blow through the house. Cultured and sophisticated, Teresa and her son Stefano had mingled with important artists of the time, such as Francesco Hayez, who depicted them in the fine family portrait held in the Pinacoteca di Brera, or Luigi Sabatelli, whose pen drawing of Stefano as a child in 1825 is remarkable. Teresa’s beauty and sensitivity are evident from the bust which Francesco Confalonieri made of her while she was still a young lady. Having lived in Paris with her first husband from 1819 to 1822, she had become close friends with the famous painter and illustrator Achille Devéria, who was to prove a decisive influence in her cultural development. Teresa and her son put together a magnificent, up-to-date library, stepping up their purchases after she married Manzoni. The library is particularly well-stocked in novels, travel books and volumes of general interest, many of which are illustrated. Significant in this respect is the presence of the most important illustrated French editions, novels and satirical series. For instance, alongside the instalments of La Caricature or Charivari, we find the mythical creations of the 1830s, by Devéria himself, Grandville, Daumier, Cham, Gavarni, Malapeau and Doré.

There are some fine examples of these books here, all handsomely bound, which would serve as the model for the new edition of The Betrothed, illustrated by Francesco Gonin and published in instalments between November 1840 and November 1842. Teresa played an important role in this enterprise, a major achievement in the Italian publishing scenario, guiding and accompanying her husband through the process. In this way a modern image was created for the novel, much closer to Manzoni’s intentions than the previous illustrations which he did not like, such as the lithographs by Gallina and the great Roman artist Bartolomeo Pinelli shown here, which were excellent technically but not a faithful representation of the spirit and atmosphere of the novel, portraying it instead as a picturesque kind of popular drama.

Room 5

The bedroom

«The spacious bedroom is furnished sparely and with striking simplicity. The walls are lined with flowered wallpaper, white and pale yellow, while the centre of the ceiling is decorated with a fresco depicting a bunch of large roses. Above the bed hangs a small painting of a religious scene and a little crucifix. On the wall to the right of the bed hangs an oil painting, small and unframed, which is a portrait of Manzoni’s closest friend Luigi Rossari, who died two years ago, and on the same side, beyond the fireplace, a fine oval portrait of the Holy Family, painted on copper. On the facing wall, above a small sofa covered in blue and white woollen material, is an image of the Virgin Mary contained within a gold frame.

Five or six simple chairs are scattered around the room; facing one of the two windows which occupy the fourth wall is Manzoni’s favourite, old-fashioned armchair which is upholstered in leather. In the centre of the room is a modest round table made out of walnut wood and topped with yellow marble. Above the fireplace is a mirror, with two brushes on the mantlepiece, one for combing the beard, and the other a hairbrush».(«Illustrazione popolare, 29 May 1873»)

Room 6

The writer of writers

... He wanted to speak as a man to men, just like those that had something interesting to say spoke. His companion in this undertaking of rubbish was another Count, a contemporary of his, a imiserable and scrawny person. The words of the latter are spectrally clear: «The night is sweet and clear». ... Elevated thoughts close the marvellous poem «Adieu Cecilia! Rest in peace». ...

Don Alessandro nobody will ever give us a new edition of your tale! But if they did, we would ask: «Don Alessandro, do not describe private problems so cruelly; do not interpret so acutely, for the purpose of sublime admonishment, the facts that are apt to be expressed in the rhetoric of the times. Let Renzo be a clever libertarian, at least let him wear a cravat like the ones the feared Communards wear in your beloved Paris. Let Lucia be not so coy, so shy, so blushing, to attract the mockery of a great of the novelist’s art. Or disguise Renzo as a racing car driver and let him declaim Nietzsche; undress Lucia and make her read Margueritte. Only then will you be able to hope for a place in Parnassus: while thus (but what have you done?) you will be relegated to the anthologies of gymnasium schools, to be used by sluggish youths with their lazy yawns. What have you done, Don Alessandro, that here in your own land where you hoped even for the charity of twenty-five subscribers, all of them took you for one poor of spirit?»

(Carlo Emilio Gadda, Apologia manzoniana, 1927)

This is an interesting foreword by the second great Lombard writer (born in the road named after Manzoni), a comprehensive introduction to Manzoni, as Carlo Dossi would say. To understand Manzoni in the continuity and new interpretations of his works, over a period of sevent years from 1802 to 1870, during the «memorable age» born of the French Revolution, which experienced, or suffered, the formation of the nation states, with the political unification of the Kingdom of Italy, and the often unperceived pulsing of social unrest whose high point is reached, as Gadda suggests to him, in the municipality of «his»beloved Paris.

The author of The Betrothed and History of the Column of Infamy asks that his novel and anti-novel be read as poetic works and essays, by a historian and linguist, as only in this way can one understand the ardous ideological tension and the fascination of the «wording», which, in the transparency of its Caravaggio-esque backdrop, says Gadda, in the pluri-expressive gradualness (the thousands of handwritten pages kept in the Braidense library bear witness to this), reaches, wrote the great scholar Giovanni Nencioni, the «sublime arising from simplicity» of his perpetual role model, Virgil (a copy of whose works Manzoni holds in his left hand in the statue located in Piazza San Fedele).

Room 7

The ‘farmer of Brusuglio’: Manzoni as botanist

The extraordinary passage in The Betrothed describing what is known as Renzo’s vineyard reveals the depths of Manzoni’s botanical knowledge. As a nobleman of the countryside he was also an expert agronomist, a common vocation among the Lombard aristocracyof the time which dated back to the age of Enlightenment, or at least became established in that period.

Having to manage his own vast estates and those of his mother, Manzoni had studied botany indepth, and developed new techniques for cultivating different species of trees, grains, vines and fruit, without neglecting gardening. He developed an interest in breeding silkworms, which too was widespread in those years, but also experimented with growing hemp and cotton. He was among those who supported the introduction of the robinia tree to strengthen riverbanks and roadbeds, a custom which, once established, was to change the rural Lombard landscape decisively.

This passion, reflected in the pages of the novel, is also documented in his letters, where he describes his experiments, asks for seedlines, and writes of the agricultural volumes which he was studying and are still kept, unchanged from his lifetime, in the library at the villa in Brusuglio, the family’s summer residence which Manzoni’s mother, Giulia Beccaria, had inherited from her partner Carlo Imbonati. The villa is still set in the grounds of a large and very fine park, which Manzoni himself redesigned as one of his favourite locations for reading and studying. From here he could see the peaks of his beloved mountains in the distance: the Grigna and the Resegone. It was in the solitude of Brusuglio that he wrote some of his most famous works, including, in July 1821, Il Cinque Maggio.

Room 8

Manzoni’s places: landscape between reason and emotion

The pictures shown here document some aspects of the city of Milan in Manzoni’s century, such as the fine view of the popular Verziere market by Alberto Dressler, or are linked to particular episodes in his life, such as Casimiro Radice’s genre painting of Cascina la Costa at Galbiate, where Manzoni was ‘weaned’. The peaks of the Grigna mountain near to Lecco, meanwhile, as shown in the two paintings by the patriot, painter and writer Salvatore Mazza – whose earlier work I bravi alla Malanotte from 1854 was inspired by an episode from The Betrothed – recall the ‘unbroken chains of mountains’ referred to at the start of the novel. The view of the lake by by Giuseppe Canella, the main protagonist of the Lombard school of romantic landscape painting in the first half of the nineteenth century, is also reminiscent of Manzonian atmospheres. A significant role was also played in this respect by Manzoni’s stepson, Stefano Stampa, a distinguished collector but also a fine amateur painter himself, having been a pupil of Massimo d'Azeglio, Manzoni’s son-in-law.

As these works show, the development of landscape painting and vedute in Lombardy during the years of the Restoration was profoundly influenced by The Betrothed, where the descriptions of places reflect both a rational approach, created by the almost topographical record of the countryside which they provide, and a more sentimental quality, where nature and environment reflect the observer’s state of mind. The first page of the novel, for example, begins with a dizzying visual descent starting from ‘that branch of the lake of Como’, and ends in the silence and melancholy of those ‘paths and tracks … which … sometimes run steep, sometimes level, and often drop suddenly and bury themselves between two walls, from which, when one looks up, only a patch of sky and some mountain peak can be discerned’; or the heart-breaking landscape depicted at dawn, which inspires both serenity and ‘sadness’ in the episode where Fra Cristoforo is followed on the emotional journey from ‘his convent in Pescarenico’ to Lucia’s house.

Room 9

Friends

‘Because, Pagani, you have not forgotten your absent friend, may heaven always keep you healthy and celibate.’ Until 1806 Giovan Battista Pagani was the friend to whom Manzoni listened. Manzoni used the same term to describe Carlo Porta, in 1836, in whose cameretta circle he came to know and appreciate Giuseppe Bossi, Gaetano Cattaneo, Tommaso Grossi and ‘il pivello’ (‘the greenhorn’) Luigi Rossari: surprisingly playful, jocular voices emerge from their written correspondence.

In 1807 Ugo Foscolo, by now virtually in exile, described himself as a ‘distant friend’ of Manzoni, though it is not known whether Manzoni replied. On 11 February 1809 Manzoni wrote to Vincenzo Monti from Paris, ‘you still have all my long-standing friendship and admiration’.

He repeated the sentiment on 2 February 1827, writing to his illustrious friend using the formal voi form of address. Until Manzoni wrote his great novel, in which Grossi and Giovanni Torti are both mentioned for their poetic merits, Ermes Visconti remained the most assiduous contributor in Manzoni’s creative laboratory, but following a profound conversion experience he left Via Morone, never to return.

Also published in 1827 was Giacomo Leopardi’s Moral Tales. Their mutual silence is a sign of how the two great Italian writers followed parallel paths, compelled not to communicate with each other. Neither Niccolò Tommaseo nor Cesare Cantù can be classed as friends of Manzoni.

Goethe, Lamartine and Poe, too, were admirers rather than friends. As Cristoforo Fabris wrote in his Memorie manzoniane, Manzoni came to need friends who would listen to him: ‘throughout his life he never had many friends ... aside from Grossi, Torti, Rosmini, Giudici, Marquis Ermes Visconti, Monsignor Tosi ... I will mention only those who were friends even in his long old age, those whose memories I cherish so dearly: the two abbots Ghianda and Ceroli, Professor Rossari, Rossi the librarian, Marquis Lorenzo Litta Modignani, Giulio Carcano, Dr Salvatore Pogliaghi, Count Gabrio Casati, Marquis Giuseppe Arconati, all of them now departed; and, among those still living, Bonghi, Professor Rizzi and Don Giovanni Visconti Venosta. ... He was deeply engaged in conversations, he was the one who talked the most; in the freedom of family conversation, and at times animated speech, his stutter – the defect which tormented him so much in the presence of strangers, even a great admirer – would virtually disappear’.

In the 1850s, apart from the many friends whose attentiveness is recorded in Colloqui col Manzoni, he discussed and debated most with Antonio Rosmini.

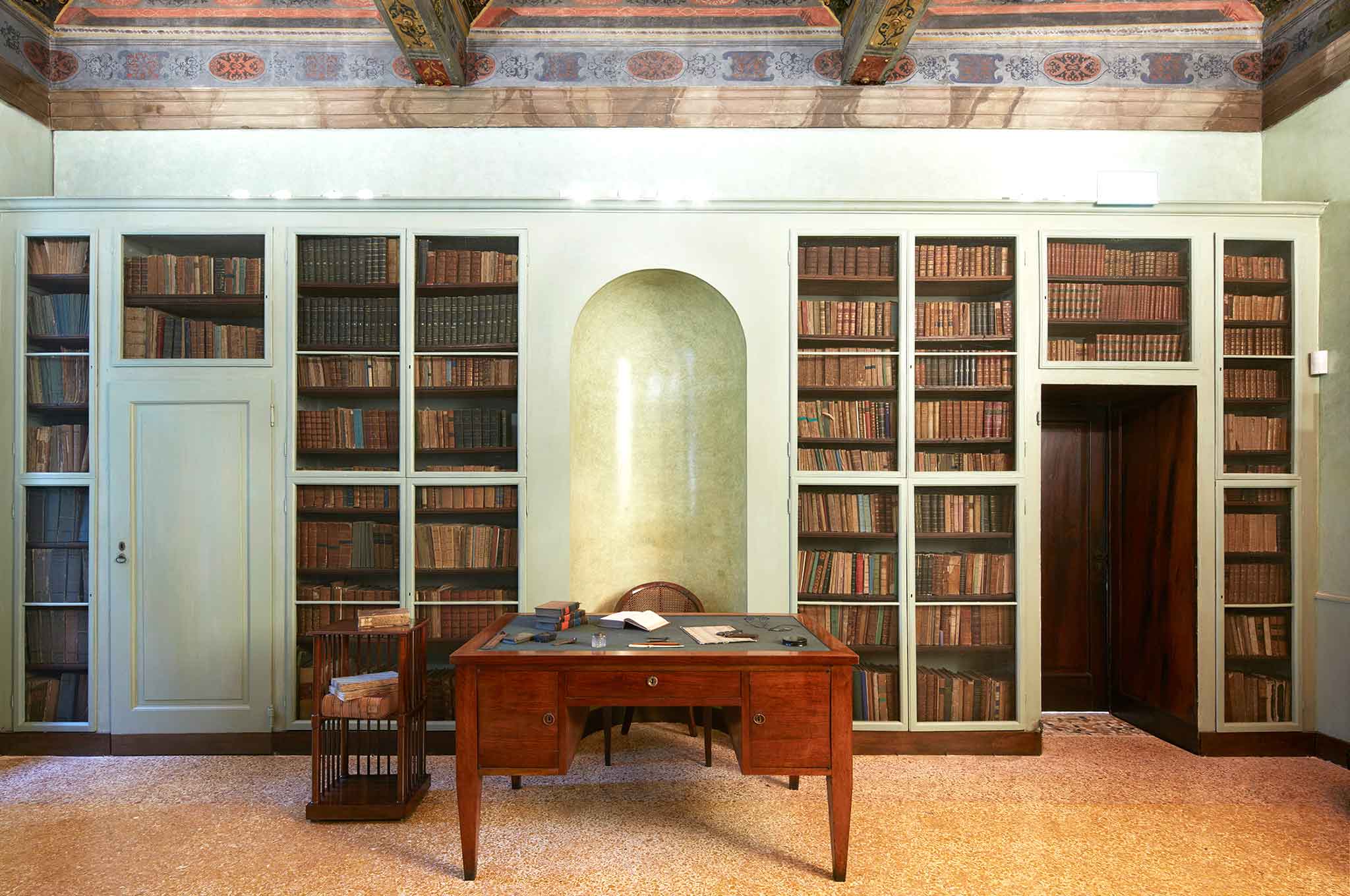

Room 10

The study

‘Whoever in those days turned into Via del Morone from Piazza de' Belgioioso to reach Casa Manzoni (which still retained the rundown façade of the previous century), crossed the courtyard and the portico opposite, to seek the poet on whom fortune was beginning to smile, would have seen him in his study on the ground floor, to the left of a passageway leading into a small garden.

This study, the walls of which are still today lined with around a thousand books (the classics ancient and modern, and works by historians and philosophers of every age and nation), and the garden, shaded by the odd ancient tree with flowering shrubs scattered here and there, were the poet’s refuges from near the turn of the century. There he was able to let his tireless mind and thoughts run free. The other study opposite his belonged to Tommaso Grossi, who was like a brother to him and who lived in the same house’ (Giulio Carcano, 1873)