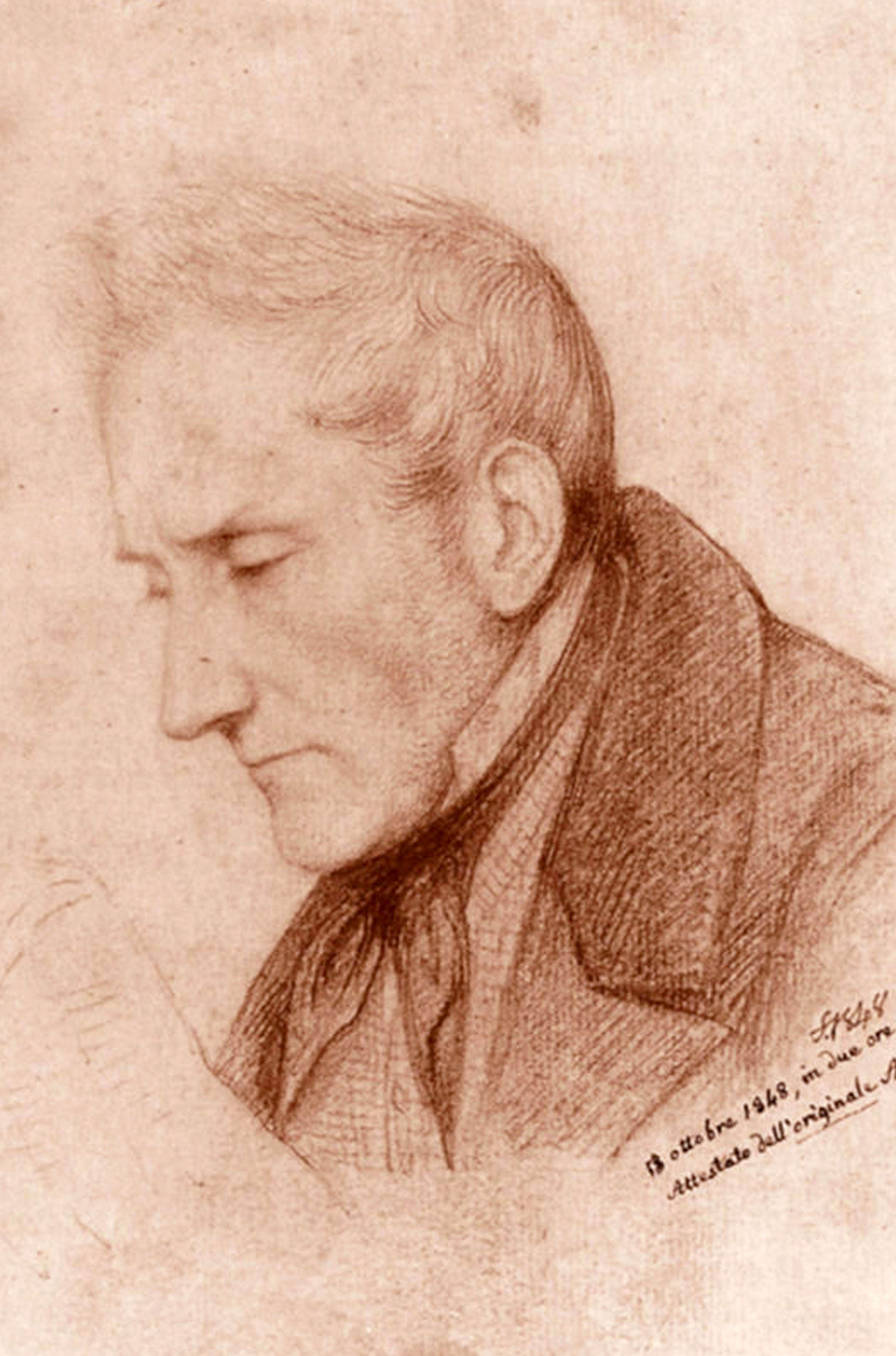

Manzoni

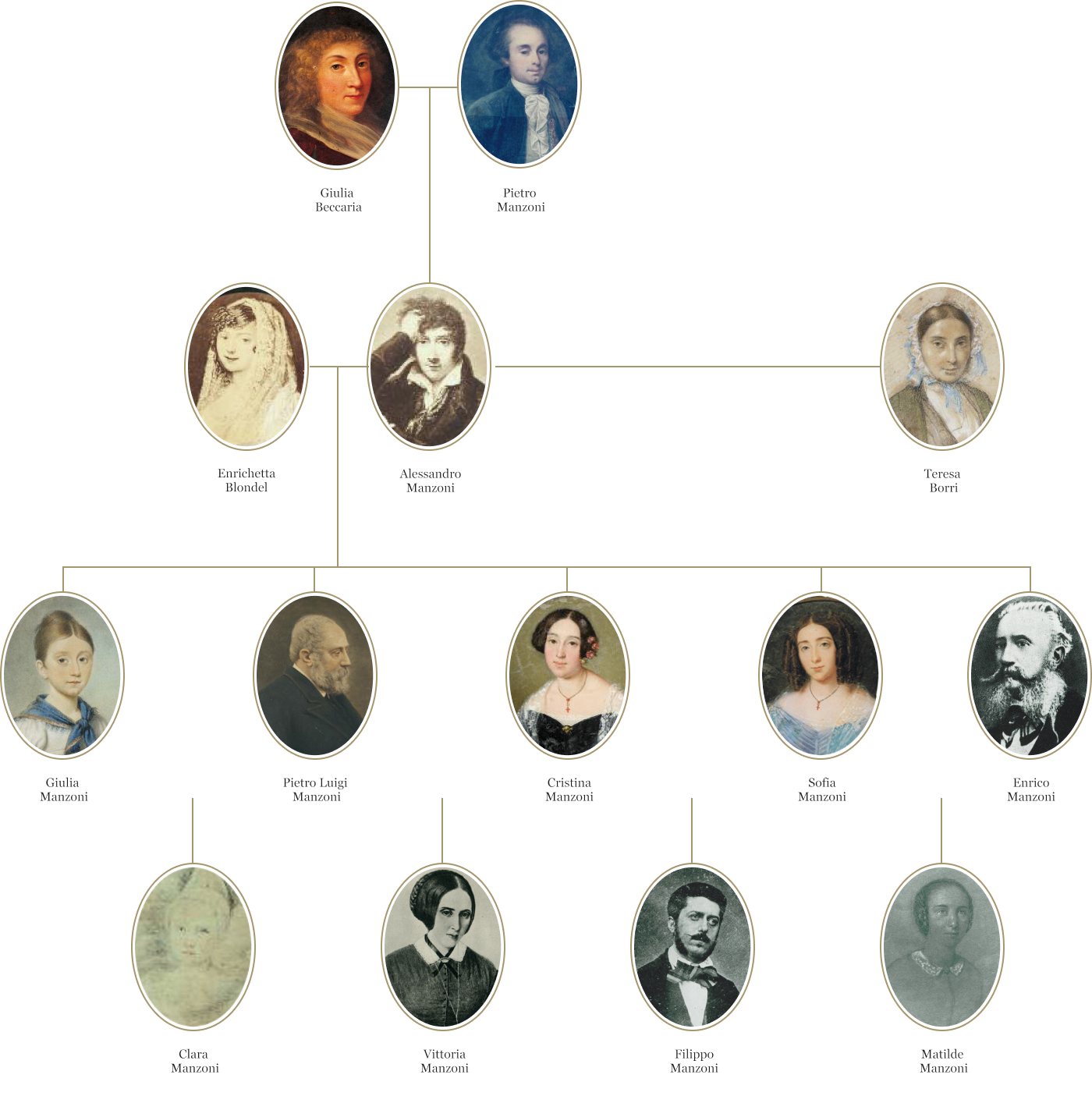

The Manzoni family

Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794)

Manzoni’s grandfather was, along with the Verri brothers, one of the leading representatives of the Lombard enlightenment. He was a contributor to the famous literary journal Il Caffè, and in 1764 wrote the work Dei delitti e delle pene, to which he owed his fame. For fear of reprisals, the treatise was published anonymously in Livorno. The work, which explains the barbarity of torture and the death penalty, was indeed put on the proscribed list in 1766, but still enjoyed widespread success among intellectuals all over Europe.

With his wife Teresa de Blasco Cesare Beccaria had two daughters: Giulia and Marietta. Relations with the eldest were strained, however, and became damaged beyond recovery following the death of Giulia’s mother and younger sister. Giulia ended up suing her father over her mother’s inheritance. In her memoirs she accused him of granting her an inadequate dowry, forcing her to marry a man who, in her words, inspired in her feelings of ‘dread and repugnance’. Cesare died suddenly of a stroke in November 1794, and eventually Giulia reached a settlement with his second wife Anna Barbò.

Manzoni met his grandfather only once, before leaving for boarding school. He later recalled him struggling to get up to offer him a box of chocolates.

Pietro Manzoni (1736-1807)

When Count Pietro Manzoni married Giulia Beccaria in 1782, he was 46 years old.

A wealthy widower with no offspring, Don Pietro lived in a house by the Navigli in Milan with his seven unmarried sisters, who included a former nun, while one of his brothers was a canon at the cathedral in Milan. Giulia, who was used to frequenting the intellectual circles of the Lombard enlightenment, was not enamoured of her conservative and clerical husband’s ‘holy zeal’ (as she put it in a letter to Pietro Verri). The boredom of family life, the hostility of her sisters-in-law, and the pokiness of the house by the Navigli did not improve even with the birth of her son Alessandro, named after his paternal grandfather. In a bid to overcome the contempt in which Giulia held his modest social condition, Pietro asked his brothers to introduce him to the upper nobility of Milanese aristocratic society, but the attempt failed, and the couple separated on 23 February 1792. He was given custody of the child, whom he sent to boarding school for his education.

Following the arrival of the French troops in 1796, he retired to a solitary life in his villa in Caleotto, away from the upheaval in Milan. Don Pietro died in 1807, having made Alessandro his sole heir, and having left Giulia ‘two diamond pendants as a mark of my esteem’.

Giulia Beccaria (1762-1841)

Daughter of Marquis Cesare Beccaria and Donna Teresa de Blasco, Giulia, along with her sister Marietta, had an unhappy childhood marked by the absence of their mother, who was always travelling and taken up with her social life. When Teresa passed away Cesare remarried, and Giulia was sent to a convent where the only visits she received were those of her father’s friend Pietro Verri.

Aged eighteen, Giulia, now a beautiful, green-eyed redhead, left the convent and fell in love with Pietro Verri’s younger brother Giovanni, whom, however, she was not allowed to marry on account of her being considered not wealthy enough. In 1782 she was married off to Pietro Manzoni. Three years later Alessandro was born: the biological son, however, of Giovanni Verri.

In 1796, some years after separating from her husband, Giulia left for Paris where she finally found happiness. Living with her beloved Carlo Imbonati, a wealthy and handsome man held in high esteem, and thanks to her famous surname, she was welcomed into the city’s intellectual circles with open arms. A few years later, in 1805, Giulia, who had been absent during Alessandro’s early years, asked him to come and live with her in Paris; and from then on mother and son were inseparable, until ‘Donna Giulia’ died in 1841.

Enrichetta Blondel (1791-1833)

Enrichetta Blondel was born at Casirate D’Adda in 1791. Her parents were Francesco Blondel, a Swiss silkworm breeder, and Maria Mariton, a native of the Languedoc region of France.

Giulia Beccaria saw her as the perfect bride for her son, while Manzoni himself, writing to Fauriel in 1807, decribed Enrichetta as a young lady who was ‘très gentille’, consumed entirely by ‘sentiments de famille’.

The couple were married in February 1808, in a very simple Calvinist ceremony which caused quite a stir in the city: for a nobleman, related to a high-ranking clergyman to marry a Protestant was unheard of. Upset by the malicious gossip, Enrichetta was more than happy to move to Paris, where on 2 April 1810, during the chaos of the celebrations for Napoleon’s marriage to Marie Louise of Austria, Manzoni underwent a sudden religious conversion.

On 22 May, deeply affected by her husband’s new-found faith and under the spiritual guidance of Degola and Tosi, Enrichetta too decided to renounce Calvinism, at the cost of severing relations with her strict mother, who accused her of committing the ‘greatest of all errors’.

Her death, on Christmas Day in 1833, plunged her husband, mother-in-law and nine children into deep sorrow. Manzoni wrote an epigraph describing her as an ‘incomparable daughter-in-law, wife and mother’, and expressed his grief in the hymn Natale 1833, composed in 1834 but never completed.

Teresa Borri (1799-1861)

Teresa Borri was born in Brivio in 1799, the daughter of Cesare Borri and Marianna Meda, both of whom were from aristocratic but not wealthy families. Aged 19 she married Count Stefano Decio Stampa. From their marriage a son, Giuseppe Stefano, was born in 1819, but she was left a widow just one year later.

In 1827, having read The Betrothed, she confided enthusiastically to her mother that the novel’s author must have been ‘truly a man after her own heart’. She requested Luigi Rossari as tutor for her son, who introduced her to Tommaso Grossi. Manzoni, who in the meantime had clearly not resigned himself to his status as a widower, was struck by the flattering description of Teresa which his friend Grossi gave him.

They were married on 2 January 1837. Thus Teresa became part of a large household, and made every effort to establish harmonious relations with Alessandro’s and Enrichetta’s children.

Vittorina Manzoni’s memories, however, were as follows: ‘To tell the truth our relationship with Donna Teresa was never particularly natural. From the start she wanted myself and Matilde to call her Mother; Father, who loved her very much, was also keen for us to do so. We wanted to please her as she was very kind, and him too ... So would write the word but we could never bring ourselves to say it!’.

Aged 46, Teresa, whom the doctors believed to be suffering from cancer, gave birth to twin baby girls: one was stillborn, the other died soon after. Manzoni kept a lock of hair belonging to the latter.

Manzoni’s second wife died on 23 August 1861.

Luigia Maria Vittorina (1811)

Luigia Maria Vittorina Manzoni was born and died on the same date, 5 September 1811, in the villa at Brusuglio.

Manzoni composed a Latin epigraph for her as follows: ‘Immature nata illico praecepta – coelum assecuta’.

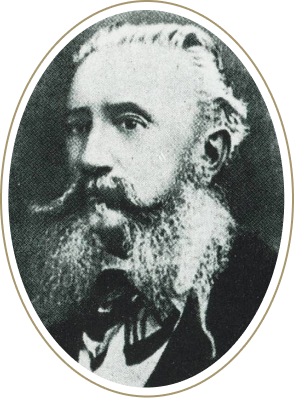

Pietro Luigi Manzoni (1813-1873)

‘On the 21st [July], at seven o’clock in the morning, our dear, beloved Enrichetta made me a present of a handsome big boy, on exactly the same day I was born and in the same house I was born in’. This was how Donna Giulia told her uncle Michele de Blasco the happy news of the birth of Pietro Luigi, whom his grandmother preferred to call Pedrino, or ‘el Pedrin’, instead.

A level-headed young man, Pietro studied philology and linguistics, but also economics and agriculture. His father came to rely on him considerably, entrusting him with various duties, such as looking after the family estate, revising the proofs of his novel, and checking the work done by the printer.

Their relationship suffered a major setback in 1845 when Pietro secretly married Giovannina Visconti, a dancer at La Scala. Within a few months, however, even Manzoni grew resigned to his son’s marriage, which was to give him four grandchildren: Vittoria, Giulia, Lorenzo (who later became an explorer) and Alessandra.

Much to his father’s sorrow, ‘his beloved Pietro’ died on 28 April 1873.

Cristina Manzoni (1815-1841)

‘Ma petit noireaude’ is what Enrichetta used to call Cristina, the only one of her girls to have dark rather than fair hair. High-spirited and passionate, as a young woman Cristina fell deeply in love with Cristoforo Baroggi, son of the notary Ignazio. Her intense love was reciprocated by Cristoforo but initially opposed by his father, who considered her dowry insufficient in view of his son’s love of spending. Cristina rejected two marriage proposals out of love of Cristoforo: one suitor the son of one of Giulia her grandmother’s friends, Henri Falquet-Planta, the other a businessman from Cremona later on.

These are the words with which she expressed the depth of her feelings for her lover: ‘Remember, my Cristoforo, that your Cristina would a thousand times choose death rather than abandon you, remember that whatever obstacles may oppose her love, it will remain the only purpose of her life, remember that a thousand times she vows never to be anything but all yours’.

After a few years, following the intercessions of grandmother, uncle Beccaria and cousin Giacomo, Baroggi gave his consent to the wedding, held on 2 May 1839. The daughter born to them on 13 February 1840 was named Enrichetta by the couple, after her maternal grandmother.

Theirs was a happy marriage, brought to an end by Cristina’s premature death. In the epigraph Manzoni composed for her he described her short life thus: “immaculate, pious, loving”.

Sofia Manzoni (1817-1845)

Whereas Giulia was schooled at home by a governess, the education of Cristina and Sofia was entrusted by Manzoni to Giovanni Torti, who was a frequent visitor to the house in Via del Morone.

On 5 December 1838, with the approval of both families, Sofia married Marquis Lodovico Trotti Bentivoglio, whom Teresa Borri described to her son Stefano as being ‘so good-natured, kind-hearted, affectionate, brave, proud and sweet, that Sofia is truly very fortunate to have him’. Her husband, who had been captain of the cavalry in Moravia and Bohemia, gave Sofia four children, Antonio (known as ‘Tognino’), Alessandro (Sandrino), Giulio and Margherita.

Sofia, naturally warm and caring, was very close to her many siblings, in particular her favourite Enrico, and Vittoria, whom she visited often. Together they frequently stayed at her brother-in-law D’Azeglio’s house, even after Giulietta’s death. Sadly, though, she shared Cristina’s fate: enjoying a happy marriage but dying young, cared for tenderly by her husband, on 31 March 1845.

Enrico Manzoni (1819-1881)

The second ‘big boy’ in the Manzoni family was born on 7 June 1819, and was taken to Paris in September of the same year. This second period spent in Paris did not turn out to be particularly happy for Alessandro, beset by his own ill health and the health problems of his youngest child, too, who was delicate and sickly.

In the spring of 1842, aged 23 years old, he married the extremely wealthy and aristocratic Elena Redaelli, who brought with her a very generous dowry of Lit. 300,000 and a sumptuous villa at Renate, where Sofia often came to stay with her family. Sofia was in fact the only member of the family to approve of Enrico’s wedding, whereas the other Manzonis were concerned that Enrico would squander his estate, encouraged by his wife who was supportive of his ambitions. Enrico was active in the silkworm trade, and had no qualms over getting into ever riskier ventures, so much so that more than once he ended up asking for an advance on his inheritance from his grandmother Giulia. His financial situation worsened around 1855, when his creditors applied directly to his father.

Enrico and Emilia had nine children: Enrichetta, Alessandro, Matilde, Sofia, Lucia, Eugenio, Bianca, Lodovico and Emma.

He and Vittoria were the only ones of Manzoni’s children to outlive their father.

Clara Manzoni (1821-1823)

Manzoni’s seventh child was born on 12 August 1821, and after giving birth a very fragile Enrichetta almost died of puerperal fever. The mother survived but ‘poor dear little Clara’, as Manzoni wrote to Fauriel, passed away on 1 August 1823.

Vittoria Manzoni (1822-1892)

Compared to her sisters Vittoria was a very healthy child, and thrived so much that in fact her step-brother Stefano nicknamed her ‘le petit écureuil’ (the little squirrel). Soon enough, however, the repeated family bereavements made her sadder and weakened her physically.

After completing her studies in boarding school, Vittoria returned home and began accompanying her father on his journeys to Tuscany. Here Giuseppe Romanelli, a Law professor, introduced her to his colleague Giovan Battista Giorgini, ‘a person of great worth, highly esteemed in Tuscany, whose adoration of Father borders on idolatry’ (excerpt from a letter from Vittoria to her brother Pietro).

Vittoria married Bista Giorgini, who had in the meantime become one of Manzoni’s teachers and advisors in the painstaking operation of updating the language of the novel to reflect spoken Florentine, in Nervi on 27 September 1846.

Their marriage produced three children, Luisa (‘Luisina’), Giorgio (‘Giorgino’) and Matilde (‘Matildina’, who aged two knew all the characters of her grandfather’s novel off by heart).

Like Enrico, Vittoria spared her father the sorrow of having to compose a memorial inscription, passing away in 1892.

Filippo Manzoni (1826-1868)

Of all his children Enrico and Filippo were the ones to cause Manzoni the most grief and heartache. When the revolts broke out in Milan on 18 March 1848, Fillippo enlisted in the Civil Guard, on the day of his twenty-second birthday, encouraged to do so by Manzoni himself. He was arrested by the Austrians at the Broletto, and deported to Kufstein in the Tyrol, where he remained until mid-June. Released from prison he was then transferred to Vienna on probation. Here the young man took on Lit. 3,600 in debt, but was bailed out by his father, who was well aware of his son’s ‘fatal predisposition’ to overspending.

After discovering that Filippo intended to mortgage the income from his grandmother’s and mother’s inheritances, the relationship between Manzoni and his son deteriorated further, to the point where the possibility of legal interdiction was raised.

When Enrico married on 10 June 1850, his father refused even to meet his daughter-in-law, Emilia Catena. Emilia bore Enrico four children, Giulio, Massilmiliano, Cristina and Paola. Burdened by debt, Filippo asked his brother Enrico for help and hospitality, but left Enrico’s house at Renate following a heated argument. At this point he begged his stepmother Teresa for help, who had no choice but to show her husband the letters.

Enrico spent the rest of his life in Milan, living by whatever means he could and with the money Manzoni sent every month. He never had the joy of introducing his father to his wife and children.

Matilde Manzoni (1830-1856)

Alessandro’s and Enrichetta’s last child was born on 13 July 1830 in Brusuglio. When she was five years old she was sent to the Monastero della Visitazione in Milan, where she was welcomed with maternal tenderness by her sister Vittoria, who had left the boarding school in Lodi following her mother’s death. In later years she would again often go and stay with Vittoria, by then married to Giovan Battita Giorgini, in Tuscany.

A melancholy soul, Matilde used to confide her inner turmoil and profound sadness at not having experienced a mother’s affection to the pages of her beloved diary: ‘Ma jeunesse s’écoule sans les regards et sans la tendresse d’une Mère’ reads the entry dated 24 March 1851.

She did not marry, and died in Siena on 30 August 1856, at the age of twenty-six. Manzoni, who could not bring himself to visit his daughter who asked for him from her sick bed, wrote of her in a touching epigraph: ‘She left behind the longing for her wonderful life, full of all the virtues that ennoble her sex’.

The sections on the Life of Manzoni, Works, and The Manzoni Family were written by Jone Riva, with the assistance of Sabina Ghirardi.